Using Risk Scores, Stratification for Population Health Management

Risk scores and risk stratification techniques are foundational for any successful population health management program. What are some of the considerations for developing this data?

Source: Thinkstock

- Population health management requires providers to maintain a delicate balance between taking a long view of generalized patient trends and focusing personal attention on the individual and the distinctive circumstances that will influence her journey towards better health.

While the two actions seem contradictory on the surface, they are in fact very closely complementary. Instead of dragging providers in contrasting directions, the global perspective can inform, guide, and help predict individualized care.

By using big data and large sample sizes to better understand patterns of what is likely to happen to individuals, organizations can develop insights into how each unique patient is progressing along common disease trajectories and plan their interventions accordingly.

There are as many population health management strategies as there are healthcare providers – and just like with patient care, there’s no such thing as “one size fits all.”

However, successful population health initiatives have a few commonalities, including a firm grasp on the basics of big data analytics, information governance, and how to formulate and leverage the risk scoring and risk stratification techniques that help providers organize the complex needs of their patients.

What is a patient risk score?

At its fundamental level, a risk score is a standardized metric for the likelihood that an individual will experience a particular outcome.

In healthcare, these outcomes can include service utilization events, such as hospital admissions and emergency department visits, or the development of a certain clinical state, such as heart disease, diabetes, cancer, or sepsis.

Organizations can develop risk scores by examining large cohorts of patients with similar characteristics, extracting key clinical and lifestyle indicators from those cases, and using algorithms to chart how those factors influence ultimate outcomes.

They can then compare other patients exhibiting similar clinical patterns to the validated historical data, which may help predict what will happen in the future.

“Risk score” and “risk stratification” – the act of dividing patients into “buckets” of risk based on their clinical and lifestyle characteristics – are often used interchangeably, although the two terms can have different connotations.

A risk score may indicate the likelihood of a single event, such as a hospital readmission within the next six months, while a risk stratification framework may combine several individual risk scores to create a broader profile of a patient and his or her complex, ongoing needs.

Healthcare payers and providers both use risk scores to estimate costs, target interventions, gauge a patient’s health literacy and lifestyle choices, and try to prevent patients from developing more serious conditions that could result in higher spending and worse outcomes.

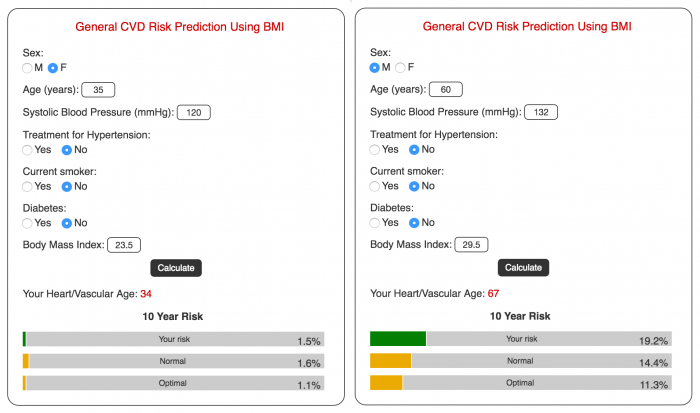

One of the most famous and well-developed examples of a scoring methodology is the Framingham Risk Score for cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Developed from a decades-long study of thousands of patients overseen by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the score aims to predict the likelihood of a cardiovascular disease diagnosis within ten or thirty years.

Using accessible metrics such as age, diabetes status, smoking history, cholesterol levels, and body mass index (BMI), patients can easily compute their CVD risk scores themselves through a number of freely available online calculators.

Source: Framingham Heart Study / NHLBI

The Framingham Heart Study, started in 1948 and continuing to this day, has contributed significantly to the healthcare industry’s understanding of how patient characteristics contribute to individual risk.

“In the past half century, the study has produced approximately 1200 articles in leading medical journals,” the study’s website states. “The concept of CVD risk factors has become an integral part of the modern medical curriculum and has led to the development of effective treatment and preventive strategies in clinical practice.”

In addition to changing how providers view heart disease, the theory of predictive analytics based on patient characteristics now underpins the majority of systemic reform efforts and is making the transition to value-based reimbursement a feasible task.

Leveraging Risk Stratification for Population Health Management

The Difference Between Big Data and Smart Data in Healthcare

How risk stratification can help providers succeed with value-based care

Improving the health of populations, reducing costs, and delivering a quality patient experience are the three components of the Triple Aim.

All three require the ability to stratify patients by risk in order to identify and address high-priority issues that impact larger groups of patients, forestall or avoid costly events, and ensure that individual needs are met in a timely and efficient manner.

“Across all [reimbursement] models, the identification, stratification, and management of high-risk patients is central to improving quality and cost outcomes,” stated the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) in a recent report on identifying high-risk patients.

“The use of predictive modeling to proactively identify patients who are at highest risk of poor health outcomes and will benefit most from intervention is one solution believed to improve risk management for providers transitioning to value-based payment.”

For providers participating in value-based care arrangements, which pair financial risk with clinical outcomes, success in these key areas can help to avoid penalties for quality and stay on the positive side of shared savings or bonus payments.

“At Atrius Health, when we think about the uses of data and analytics in the value-based environment, the theme is trying to swim upstream to get to prevention,” said Joe Kimura, MD, MPH, Chief Medical Officer of the Massachusetts-based health system.

“That makes care less costly and more valuable, not only to the health system, but to the patients, society, and the community. The question we need to ask ourselves is how we can go upstream faster, more efficiently, and more effectively. We have to think about efficiency, effectiveness, and reliability.”

"At Atrius Health, when we think about the uses of data and analytics in the value-based environment, the theme is trying to swim upstream to get to prevention."

Getting as far ahead of negative outcomes as possible is the key to successfully transitioning to a value-based world, agreed Rebecca Williams, RN, Care Coordination Management at St. Joseph Hospital.

“It’s very important to look at outcomes, but by the time we’re looking at outcomes for chronic disease, it’s almost too late,” she said at the 2016 Value-Based Care Summit in Boston.

“We want to keep people healthy. It’s very important to care for patients who are already sick, of course, but what if we could dial that back a little bit and start looking at the 30-year-old whose blood sugars are just starting to tip over the edge?”

“You want to start looking at risk stratification, predictive analytics, and being able to proactively address the future instead of reacting to the past” to begin seeing financial rewards from participating in value-based initiatives, she said.

The Top 3 Planning Pain Points in Healthcare Big Data Analytics

Understanding the Value-Based Reimbursement Model Landscape

First steps for developing population health risk scores

Shifting from the fee-for-service mentality into a proactive, value-driven environment built on a foundation of risk-based population health management can be a daunting prospect for providers who are not used to taking a proactive approach to care.

The first step for developing a population health program that includes any sort of financial incentive is to define the group of patients for which the provider will be accountable. Setting parameters on the patients involved in a value-based arrangement allows payers and providers to understand the challenges ahead of them and agree upon benchmarks for success.

“Know your population. That’s number one,” says Chip Howard, Vice President of Payment Innovation at Humana. “Every provider has to be sure about how they are being measured and where their opportunities for improvement lie. They can’t do that without knowing their population.”

Once the organization has decided upon a population to manage, and understands the conditions, events, or costs by which they will be measured, it can start to examine the risk levels involved.

This task requires a familiarity with basic data science techniques, including how to identify relevant data sources, how to extract and normalize this data, and how to create a methodology for synthesizing information into a standardized risk score.

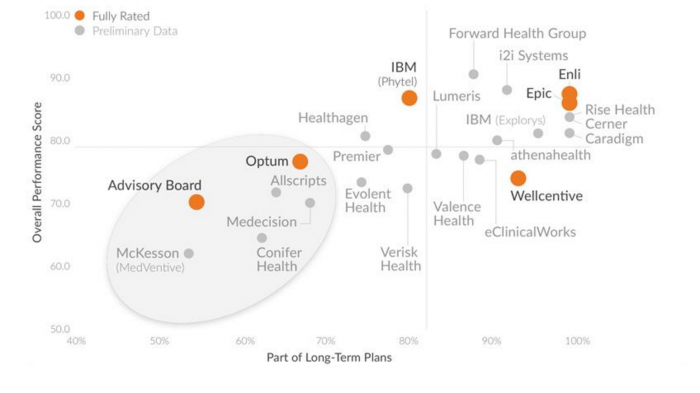

Healthcare organizations can take a shortcut through this part of the process by purchasing an off-the-shelf vendor solution for population health management, risk scoring, and risk stratification. As interest in data-driven population health picks up, the number of vendors offering innovative, cost-effective products is on the rise, says KLAS.

Source: KLAS Research

When choosing a population health management package, KLAS recommends that providers ensure the offering can meet identified core needs, gather and analyze data from disparate sources with few aggregation problems, and provide cost-effective and workflow-friendly results that will help to achieve a return on the investment.

Regardless of whether an organization is looking to purchase a vendor solution or develop their population health management tools in-house, providers must have a firm grasp on what data is accessible, how clean, complete, and accurate it is, and what it can tell clinicians about the patient story.

“Learn what data sources are available and make sure you take advantage of them,” Howard suggested. “Some payers distribute raw claims data for providers to use for analytics. That’s a great, rich source of information.”

At Community Care North Carolina, a state-wide care management initiative covering the majority of Medicaid patients in the region, claims data combines with a number of other information sources to give more than 1800 primary care practices increased insight into patient risk and population health.

“We are using statewide Medicaid claims data complemented by data from other sources, including real-time hospital admission, discharge, and transfer (ADT) data from about 80 percent of the hospitals across the state,” explained Annette DuBard, MD, MPH, Director of Informatics, Quality, and Evaluation at Community Care North Carolina.

“We are also using laboratory data and state vital statistics data to build a shared utility for the whole state to use in ways that target patients more intelligently for specific care management interventions and speed up the cycle of quality improvement. We have full visibility into Medicaid claims, including hospital utilization and pharmacy utilization, thanks to how willing the state has been to partner with us.”

Between 2014 and 2015, CCNC’s efforts produced a 5 percent drop in total Medicaid costs along with a 26 percent reduction in inpatient admissions and half the number of preventable readmissions, DuBard added.

Electronic health record data is also likely to be a mainstay of risk analytics, since the majority of clinical patient data flows through the EHR.

“Every provider has to be sure about how they are being measured and where their opportunities for improvement lie."

EHR-based risk scores have been in wide usage for years, predicting everything from dementia and diabetes to surgical outcomes and suicide risks.

However, while EHRs can be a powerful tool for predicting a specific outcome for an individual, they can fall short of meeting the larger population health management needs of accountable care organizations or providers in the same local area where each member is using a different electronic health record system.

“A person gets his or her care in a community,” pointed out Bharat Sutariya, CMO and Vice President of Population Health at Cerner Corporation. “Even in the most concentrated health system, a patient doesn’t necessarily get all of his own care in a one single health system, let alone into one single venue with one EHR.”

“Probably the greatest challenge in the industry right now is how to go beyond the four walls of the organization to get to a truly longitudinal and personal level of patient care.”

Health information exchange, on a regional, state, or national level, is often required to overcome this obstacle, says AAMC.

“HIEs can be integral data sources in event-based programs, such as readmission reduction or emergency department (ED) utilization management, by offering near real-time data to help manage a health care event and guide care follow-up,” the report states.

“High-functioning HIEs are able to provide notice of admission and lab results from hospitals within a day of patient admission so that patients are managed in a timely fashion. Discharge summaries are also shared by some HIEs quickly after patient discharge.”

AAMC also suggests that providers look to take advantage of additional clinical data sources to feed risk analytics, including local disease registries, pharmacy data, lab data, and real-time data from home monitoring devices, wearables and Internet of Things tools, or bedside monitoring equipment in the hospital.

Patient Engagement, Population Health Are Key to ACO Success

How to Get Started with a Population Health Management Program

What Big Data, EHR Vendors Do Accountable Care Organizations Use?

Enhancing risk scores with behavioral, environmental, and patient-reported data

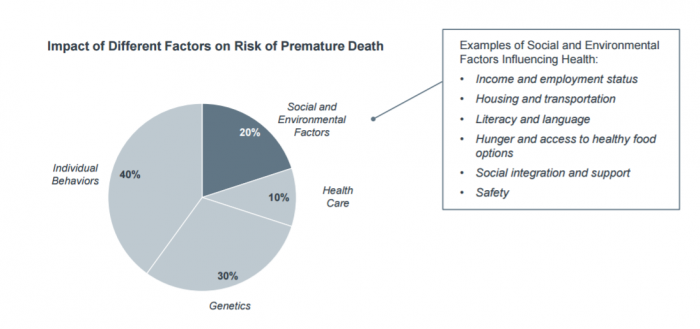

While EHR and administrative data can be excellent sources of information for conducting risk assessments, only a fraction of patient outcomes are directly related to clinical care. Up to ninety percent of patient risk is tied up in the social determinates of health, individual behavior patterns, and genetics, the Advisory Board Company says.

Environmental factors, including socioeconomic circumstances, behavioral health, and patient personality and lifestyle choices, produce significant impacts on long-term outcomes, and are necessary components of a risk stratification framework that will provide rich, comprehensive, and holistic predictions into patient health.

Source: Advisory Board Company

“It’s so critical to have the ability to piece together any and all data about the patient,” said Tina Esposito, Vice President of the Center for Health Information Services at Advocate Health Care.

“In some ways, you even want to move beyond clinical and claims data to environmental data or other sources of information that really help you better describe the patient and her challenges. Integrating multiple sources of data will help a clinician understand how best to intervene with that patient – and we are now entering the kind of care environment that makes providers responsible for that kind of population health management.”

While many risk stratification efforts focus first on cost – flagging high spenders and patients with higher-than-average rates of service utilization – historical spending isn’t necessarily the most accurate prediction of need.

For example, patients who cannot afford to engage in care may still suffer from multiple chronic diseases or acute conditions, and may in fact experience worse outcomes than patients who use services at a higher rate.

Identifying and addressing the underlying socioeconomic and environmental conditions and disparities that may hinder these individuals from accessing services could help to ensure that providers are staying in contact with patients who might be attributed to their populations but are not be able to come to the clinic on their own.

“We want local providers to understand the issues facing their service areas, and we want to give them the opportunity to drill down into some of the factors related to their work that may need improvement,” said Cara V. James, PhD, Director of the CMS Office of Minority Health.

“When you look at the mortality indicators or the prevalence rates for heart disease and diabetes, those are related to so many circumstances that occur outside of the traditional healthcare system.”

“As we continue to link socioeconomic factors to clinical care, we will be able to rethink how to address these relationships, and I believe that will help us make a meaningful impact on metrics like readmission rates or medication adherence.”

Extending population health management into the community could give providers information about patient experiences that is hard to collect in any other manner, asserts a data brief by the PwC Health Research Institute.

“When you look at the mortality indicators or the prevalence rates for heart disease and diabetes, those are related to so many circumstances that occur outside of the traditional healthcare system.”

In Brownsville, Texas, for example, community health worker supplement clinical care while also collecting and reporting on environmental data that would otherwise be inaccessible/

These community advocates deliver data on the availability of public transportation, housing instability, and religious practices while connecting to patients in their own environments with cultural sensitivity and a personal touch.

Not all healthcare providers or public health departments have the ability to recruit a large workforce to gather socioeconomic data, and the availability of standardized environmental and community-based datasets is still scarce.

But as providers expand their big data analytics capabilities, become more comfortable with the extended outreach required for true population health management, and start to take advantage of “smart” environments that will collect novel sources of information, they will be able to engage in more comprehensive and patient-centered care, like in this fictional example from PwC Health.

Source: PwC Health Research Institute

With a focus on individual needs fueled by data from previous successes and patient outcomes, providers should start to develop the partnerships within the community that will enable them to conduct meaningful, coordinated, and cost-effective outreach.

Creating risk scores that include a blend of social, behavioral, and clinical data will help to give providers the actionable, 360-degree insight necessary to identify patients in need of proactive, preventive care while meeting value-based reimbursement requirements and improving outcomes across the care continuum.

Addressing Opioid Abuse with Analytics, Population Health Strategies

Balancing Access and Insight for Healthcare Big Data Analytics