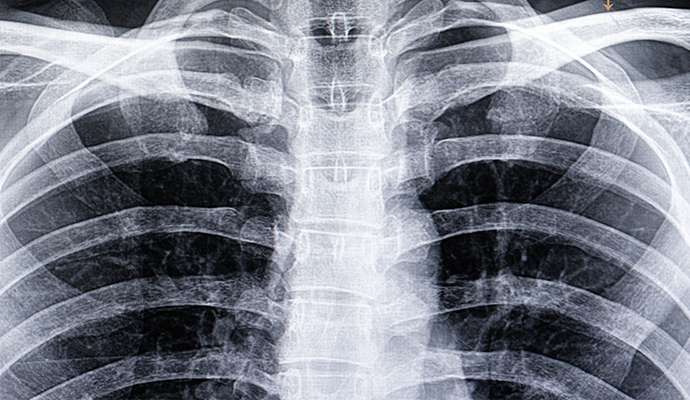

Artificial Intelligence Can Help Radiologists Diagnose Lung Disease

Artificial intelligence tools could help radiologists classify the severity of lung disease and track treatment progress.

Source: Getty Images

- Using artificial intelligence technologies, radiologists could augment their ability to objectively evaluate and treat lung disease, according to a study published in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

Lung conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are extremely prevalent in the US and around the world, researchers noted. Emphysema, a type of COPD, is characterized by the permanent overinflation of the terminal bronchioles and the destruction of bronchial walls.

Providers can evaluate the pathologic change of emphysema with quantitative CT scans by measuring the low-attenuation volume (LAV) of the lung. However, diagnosing and classifying the severity of emphysema is a difficult, unstandardized task, and scans of damaged lungs have only recently become helpful to radiologists.

“Everybody has a different trigger threshold for what they would call normal and what they would call disease,” said U. Joseph Schoepf, MD, director of cardiovascular imaging for MUSC Health and assistant dean for clinical research in the Medical University of South Carolina College of Medicine.

“In the past, if you lost lung tissue, that was it. The lung tissue was gone, and there was very little you could do in terms of therapy to help patients.”

Recent advances in treatment have brought an increased interest in objectively classifying emphysema, which is where artificial intelligence and medical imaging could make a significant impact.

“Artificial intelligence is rapidly entering the field of radiology, and AI-based algorithms may well be suited for tasks such as pattern recognition on chest CT images,” researchers said. “Additionally, these algorithms may save time, reduce variability, enhance objectivity, and be truly quantitative, creating an advantage over manual and semiquantitative methods.”

The team set out to compare an AI algorithm with traditional lung function tests, which measure how forcefully a person can exhale. Researchers examined the chest scans and lung function tests of 141 people. Chest scans aren’t currently part of the guidelines for diagnosing COPD, because there hasn’t been an objective way to evaluate scans.

The results showed that the AI algorithm provides results comparable with lung function tests, which demonstrates the potential for chest scans to quantify the severity of lung disease and track the progress of treatments.

With AI, providers could objectively evaluate scans and receive support in assessing the value of new treatments or drugs. The technology could work alongside radiologists and augment their clinical expertise.

“Taking away manual, repetitive tasks, like those that require a lot of measurement, is of great benefit to a radiologist, especially when reading cases that may have 20 or more nodules,” said Philipp Hoelzer, customer engagement manager with Siemens Healthineers. “Interpreting the images, and the abstract thinking that goes along with it, will remain with the radiologist.”

AI algorithms could also create 3D models of patients’ lungs, showing existing damage and helping patients understand the necessity of making changes.

“If you could visualize it and provide the information in image terms, you could better communicate with the patient and hopefully nudge the patient into smoking cessation or lifestyle changes,” Hoelzer said.

Artificial intelligence also has the potential to find things that humans may not see, the researchers noted.

“We're told the patient has these types of symptoms, and then we basically go look for stuff that could explain those symptoms. So, we’re often blind to things that do not necessarily relate to the organ system we’re interested in,” said Schoepf.

Researchers want to see whether the algorithm could improve patient management by detecting problems earlier, like a widened aorta or decreased bone density. The team will test the tool for three more months before deciding whether to deploy it more extensively. The group believes it could help standardize care.

“It's a great chance for patients to get better care. We have world-class radiologists here, but these systems add a little extra,” said Schoepf.