How Geographic Data Can Help Address Social Determinants of Health

An individual’s zip code is more predictive of her health than her genetic code, but it’s not just zip code data that can help tackle social determinants of health.

Source: Getty Images

- A patient’s social determinants of health contribute more to her health than her genetic code or her medical care. These social determinants of health are factors outside of the traditional healthcare setting that impact an individual’s health (e.g., food insecurity, transportation, job training, and housing). To combat these social determinants of health, payers are providing housing grants to their members most in need, ridesharing companies are offering rides to patients for non-emerging medical visits, and Medicare and Medicaid are considering covering healthy food plans.

The goal is to mitigate the negative impact of these socioeconomic factors, but many in the healthcare field are left wondering what data can inform decisions on how to tackle these problems in their communities.

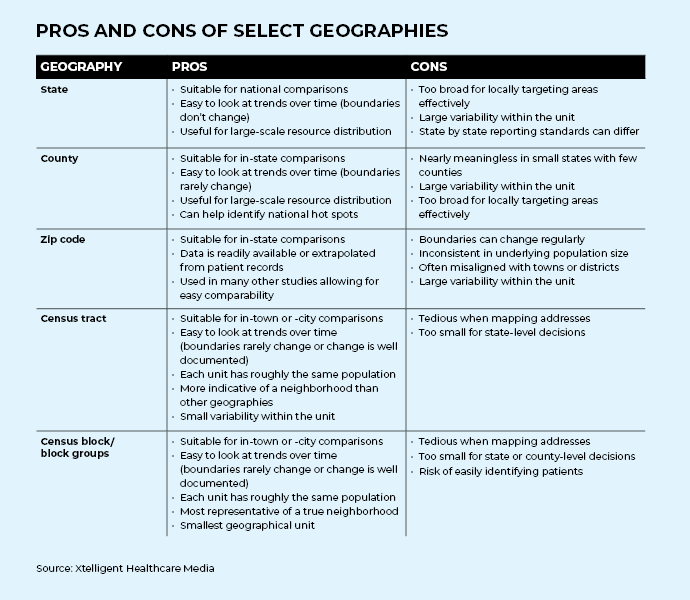

Historically speaking, zip code data is the most widely used geographic data to help understand the needs of a population, but it is not necessarily always the best data to do so. Many different types of geographic data exist to support the development of a strategy to address social determinants of health in a population. A patient’s census tract might be the best data source to help implement this strategy in a meaningful way.

In order to use geographic data to successfully achieve an organization’s goals around social determinants of health, data analysts must understand the availability of different geographic data sources and define a target population. This awareness will help better understand the granularity of data needed while still ensuring patient confidentiality and ultimately help to implement a successful strategy.

Consider the Accessibility of Geographic Data

Geographic data is available in abundance, largely because of the United States Census. The purpose of the census is to accurately count the number of people in the country for the appropriate provisioning of government resources. However, this data is also widely used for public health purposes and identifying areas of high risk and need.

The geographic units in the census are hierarchical and build on one another. Several of the smallest geographical units — a census block — combine to make census block groups. These groups are in turn joined to form census tracts that make up counties, then states, and finally the nation. Census geographies are also roughly similar in size and population.

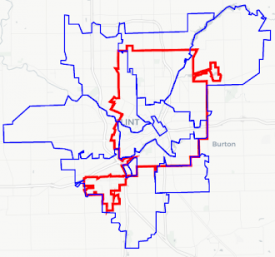

Comparison of city limits (red) and zip codes (blue) in Flint, Michigan

Source: City-DataHowever, there is a second common geographic unit used in analysis, the zip code. The United States Postal Service developed zip codes for the purposes of delivering mail. These units were not divided with geography in mind, meaning the size and number of people in each zip code is inconsistent. A zip code can range in size from a single building to several hundred square feet, from a population of zero to thousands.

To make geographic units consistent, the United States Census Bureau developed Zip Code Tabulation Areas (ZCTAs). ZCTAs generally represent the zip codes designated by USPS. However, they do not perfectly align with the traditional notion of zip codes, nor do zip codes always align well with city or town boundaries. One zip code may be in two towns which makes estimates for one town difficult.

Mismatching data can make assessing the needs of a community difficult, especially when the community under analysis is not easily defined by traditional geographic units.

To combat this problem, researchers most commonly use traditional zip code-level data under the assumption that it fully represents the community of interest. However, non-traditional geographies might more accurately represent the area of interest. Units like census tracts or school districts should not be dismissed. If researchers have access to a patient’s address, publicly available resources can map the address to other geographic units.

Define the Target Population

Geographic data is most useful for identifying hot spot areas where the population is at high risk for contracting a disease or in high need of interventions to minimize disease impact. These are areas where the average income might be well below the federal poverty level, so the residents are at increased risk of heart disease or areas in a food desert where obesity rates are higher. Identifying these communities can help target interventions to areas that will have the most impact on the greatest number of at-risk patients.

Depending on the intervention to target social determinants of health, different geographic units can be of use. If high-level budget decisions need to be made, large areas such as towns or municipalities are appropriate levels of analysis. On the other hand, if trying to determine where the most impactful location for a community garden would be, neighborhood-level data would help inform that decision best as identifying the county most in need would not help narrow down where the garden should be planted.

In many instances, the level of data available does not directly translate to solving the problem at hand. Narrowing the scope as much as the data allows and then talking to community members and stakeholders for more information would be the best strategy.

Identifying a target area for intervention will help ensure that intervention helps the greatest number of at-risk people in a selected area. When resources are limited, targeting a specific population will help an intervention to have a high level of impact and optimize an organization's investment.

Geographic Data Comes with Variety

The larger the geographic unit, the more variability within that area. The distribution of social determinants of health can vary drastically even within a single zip code. People refer to a “good” or “bad” side of town, yet these areas have the same zip code. The needs of each part of that zip code are likely very different.

Many researchers link information from an individual patient to the aggregate data of that patient’s zip code. For example, the average income level of a patient’s zip code is often assumed to be the income of that patient. It seems obvious that this individual’s income could be significantly above or below the average for her zip code, but many research studies use this method to link to unknown patient characteristics and social determinants of health indicators.

Often this method is used because it is the most accurate data that can be obtained. However, if more precise data can be used, it should be to avoid making broad assumptions about individuals.

Extrapolating a patient’s income from a smaller geographical unit, such as a census tract, would more closely represent the patient's actual income as there is less variability the smaller the unit.

Ensure Patient Confidentiality

Generally, data is publicly reported at a certain level to maintain patient confidentiality. The challenge is balancing reporting information at a meaningful level and maintaining patient confidentiality.

For example, a report on a rare disease might give statistics at a county or state level because so few patients have that disease. If this information were reported at a neighborhood level, people in the community could easily identify which neighbor the data is referring to. To preserve the patient’s anonymity, the data is reported at a higher level. On the other hand, a more common disease (e.g., high blood pressure) could be reported at a more granular level because it is harder to determine which neighbors the report is referring to.

One strategy many health departments use when publicly reporting geographic data is the rule of five. Information is not reported if there are fewer than five cases in a geographic area. This method ensures patient confidentiality but can make understanding the data difficult for end users if there are large areas with "no data to report." An end-user might find it difficult to interpret or compare this data point to other areas.

Another strategy to protect patient confidentiality is to group like individuals. For example, if reporting socioeconomic status by geographic unit is the goal, a data analyst could calculate the average for an area or break down the responses into different categories (perhaps by the percentage of the federal poverty level). Either approach helps to deidentify the data while still giving it while still helping end using meaningful interpret the information.

Patient confidentiality is often why zip code-level data is used rather than smaller geographic units like census tracts. When reporting data by geographic area, patients’ privacy must be a priority, especially when it comes to sensitive health and social information.

Conclusion

Geographic data is regularly used to inform strategies for addressing social determinants of health. Most often, zip code-level data is the basis for this analysis. However, there might be better geographic units for assessment depending on the organization's goals and the accessibility of data. No data source is perfect, but the smaller the unit of geography, the more likely it is to represent the individuals in the population accurately.

A patient’s zip code might be more indicative of their health than her genetic code, but a patient’s census tract can help address her social determinants of health.