Population Health Management Strategies to Reduce Health Disparities

Health disparities are rampant throughout the healthcare industry. How can population health management strategies reduce their impact?

Source: Getty Images

- For the most part, healthcare buzzwords are associated with positive, forward-thinking change.

Terms like precision medicine, artificial intelligence, and chronic disease management imply productivity, effective transformation, and novel approaches to care delivery – all in the name of better health outcomes.

But for all the optimistic phrases floating around healthcare, there is one cloudy expression looming over the horizon: health disparities.

The reality that minority populations or lower-income individuals tend to experience a higher burden of disease, disability, and mortality is something that the pandemic has demonstrated in the harshest of lights.

While recent vaccine authorizations have offered a glimmer of hope, they’ve also brought validated concerns about distribution and access – many of which have already come to fruition.

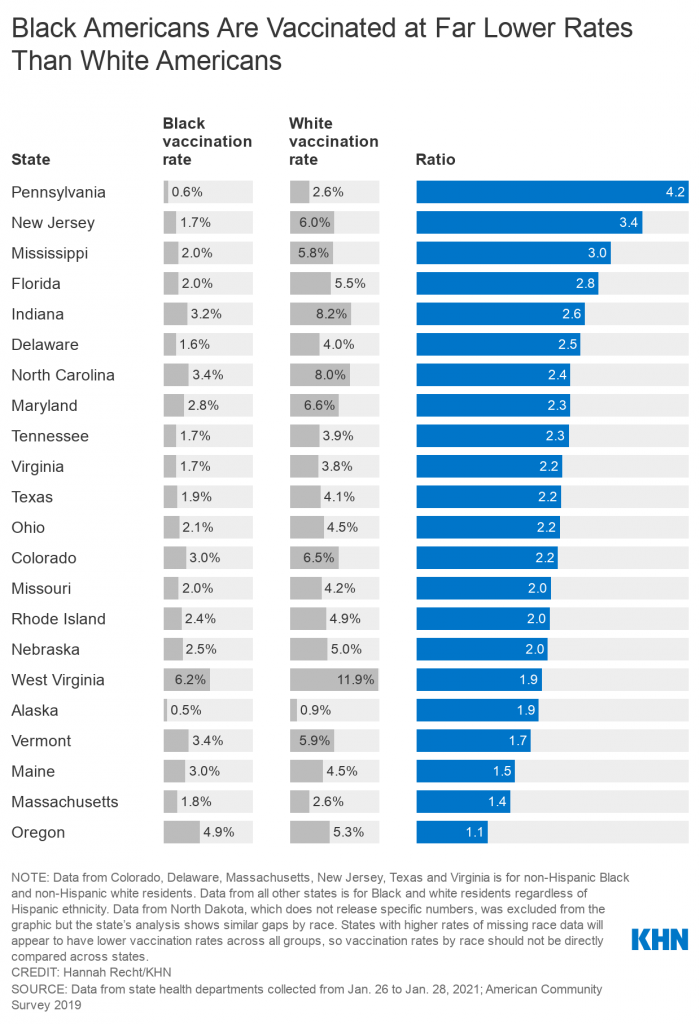

A recent report from Kaiser Health News showed that in several states, white residents are being vaccinated at significantly higher rates than black residents. In many cases, these rates are two to three times higher.

“We started worrying a little bit about vaccine distribution months ago, because we've all been here on the earth for a long time. We have an idea of what will happen if there isn't a concerted focus on equity,” Rhonda Medows, MD, president of population health management at Providence, told HealthITAnalytics.

“COVID-19 has highlighted longstanding health disparities and amplified all of these places where we had some definite room for improvement.”

Beyond the pandemic, many conditions disproportionately affect underserved populations, and certain groups consistently suffer worse disease outcomes. If the industry is truly going to drive down health disparities, organizations will need to develop enduring population health management strategies to help enhance clinical care both during and after the current crisis.

Source: Hannah Recht/KHN

Using the right data to identify the right patients

For some health systems, the pandemic offered the opportunity to ramp up existing population health management methods, using previously-collected data to refine interventions.

“At Providence, we had already begun conducting health disparities assessments for all of our patient populations – including our own employees – as well as larger community health efforts,” said Medows, who is also the CEO of Ayin Health Solutions.

“In each of our regions, we use advanced analytics and risk stratification tools to inform our clinical care teams of which populations have the highest rates of health disparities – both COVID-related and non-COVID-related, because we have to remember that there is a world beyond the pandemic.”

Medows and her colleagues collect the many data points that can impact patients’ health, like social determinants, comorbidities, and mental health issues. After giving this data to Providence’s clinical care teams, leaders use it to develop five-year strategic plans that include standard performance measures and annual interventions.

With these plans in place, care teams can begin to focus on certain populations and conditions to reduce health disparities.

“For example, maybe in one particular region the care teams decided to work with black or Indigenous people on hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, infant mortality – it could be any host of things. And since they know where the people are, they can work with community partners to design interventions,” Medows explained.

Grace Flood, UW Health

At UW Health, researchers leveraged their existing expertise to ensure equitable vaccine distribution within their organization. Together with the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, the team developed a data analytics algorithm that prioritizes distribution among people who otherwise share similar risks due to their jobs.

The algorithm uses a person’s age and socioeconomic status, derived from the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI), to measure someone’s susceptibility to severe COVID-19.

“We all recognize the risk of COVID-19 due to increasing age, but race and ethnicity are also closely correlated with higher rates of COVID-19 hospitalizations and mortality,” said Grace Flood, the director of clinical analytics and reporting in the office of population health at UW Health.

“SVI was suggested in the framework for equitable allocation of COVID-19 vaccines. The team thought that the index could help prioritize individuals living in vulnerable locations, because it incorporates 15 different social factors including poverty, crowded housing, and minority status.”

UW Health implemented the tool to equitably provide vaccine doses to frontline healthcare workers.

“We used it for phase 1A, which was made up of just our healthcare employees within risk groups,” said Flood.

“These individuals were already divided into groups based on job-related risk of exposure to COVID-19. And then within those groups, we used the algorithm to prioritize employees because we had limited amount of vaccine at the time.”

The tool is also freely available for other organizations to use to help guide their own vaccine distribution plans.

“Because it was originally meant for phase 1A, the distributions are based on populations between the ages of 15 and 74. But because age is such a dominant factor, as you increase in age the algorithm should still be very effective for any age group,” Flood noted.

Outside of COVID-19, researchers are seeking to uncover the reasons why some common conditions are more prevalent and debilitating among certain groups.

Scientists at the University of Southern California (USC) recently conducted a study examining genomic datasets from men of European, African, Asian, and Hispanic ancestry to better understand prostate cancer risk.

The team found that genetics play a significant role in the prevalence of prostate cancer among black men – a population group whose risk for the disease is 75 percent higher than it is among whites.

“The markers we identified enabled us to better define an individual man's risk of disease. We were also able to determine that ten percent of the population has somewhere between four- to five-fold greater risk of developing prostate cancer compared to those who are at average genetic risk,” said Christopher Haiman, ScD, professor of preventive medicine at the Keck School of Medicine at USC and director of the USC Center for Genetic Epidemiology.

“Additionally, we found that the aggregate of all of these genetic variants identified throughout the genome are substantially more common among men of African ancestry than among men of European ancestry.”

A major advantage of the study was its large, diverse dataset – an asset that should carry over into other research efforts, Haiman noted.

“For prostate cancer, there is strong evidence to support that genetics are a principal cause of the disparity. With other prominent chronic diseases, you can't really say that genetics play such a significant role in differences in disease incidence between populations. At least, that's based on studies to date,” he said.

“That's why it's important to continue to have larger, multi-ethnic studies. The more studies we include, the better we understand the full spectrum of genetic variation that’s contributing to risk across populations. This will also help us further understand if there are some gene forms that may be limited or more common in certain populations.”

Meeting underserved individuals where they are

To really reduce health disparities, it's not enough to just identify which population groups are most at risk. Leaders must connect with patients in order to understand how they can best meet individuals' needs.

Rhonda Medows, MD

According to Medows, this primarily involves collaborating with community organizations.

“In July, we did a formal kickoff on health equity across Providence, which includes all of our delivery systems across the seven-state footprint. We had already been measuring and researching health disparities, and we wanted to move beyond that to real action and intervention,” she said.

“This includes things like hiring individuals from the community to be community health workers, providing them with training, and having them focus on the health disparities we’ve identified. It also means formalizing community partnerships, whether with the Boys & Girls Club or a local church – it could be any number of things. We need to bring them into the fold and share the same measures and information with them.”

Providence has also implemented strategies to address minority and lower-income patients’ anxieties and mistrust of the COVID-19 vaccine.

After generations of mistreatment, and the aftermath of unethical research efforts like the Tuskegee Syphilis study, many black individuals are deeply suspicious of public health campaigns – a sentiment that extends to other minority groups as well.

The Kaiser Family Foundation recently found that when it comes to getting vaccinated, black and Hispanic adults remain significantly more likely than whites to say they want to “wait and see” how the vaccine works for other people before receiving it themselves.

This is why, while the country waits for vaccinations to become more widely available, Medows and her team are taking this time to provide outreach and education to those who may need it.

“This situation requires us to have a better understanding of why people might be fearful or hesitant to accept the vaccine. There’s a lot of education behind that. There's also education about having honest conversations with our patient populations and community groups, and having those conversations repeatedly,” said Medows.

“We have to make sure that we invite repeated questions and that we’re there for the individuals when they're making their decision about getting vaccinated. With this approach, we can move from total rejection of the vaccine to acceptance. Although they have to come to that conclusion by themselves, they can reach it with our support, patience, information, and honesty.”

The team at UW Health is taking a similar approach.

“We’re going to be hiring community health workers to reach out to more vulnerable patients by phone, email, and other forms of communication,” said Flood.

“We need to make sure that we’re reaching out to people who are more vulnerable or living in more vulnerable areas. We know that there's likely some justified fear or apprehension about getting the vaccine, so we want to be able to help allay some of those fears.”

To ensure diverse populations are represented in clinical research – and in turn, to generate evidence that can improve care for all patients – Haiman said that the solution is simple: Enroll them.

“We need to work with those populations, as well as community leaders in those populations, to help people understand the value of the work and what they're actually contributing to. We need to show these individuals why it's potentially helpful not just for them, but for future generations,” said Haiman.

“It's quite clear that we're not going to learn everything we need to know about genetic susceptibility to any disease by studying only men and women of European ancestry. We want the discoveries that come from these genetic analyses to have widespread clinical utility in the future. To make sure everybody benefits from the knowledge, we need to make sure that the studies are representative of different populations.”

Including patients of different backgrounds may also help researchers determine other elements that contribute to disease prevalence or severity.

“There's good evidence to suggest that different populations have other non-genetic risk factors, like more prevalent comorbid conditions or social or cultural elements, that need to be accounted for. Simply limiting research to one population will not provide you an answer that may be generalizable for everybody,” said Haiman.

Developing comprehensive strategies for long-lasting change

For now, it seems that COVID-19 will be sticking around for a little longer. While many health systems are doing what they can to make sure this doesn't result in dire consequences for underserved populations, others may be looking ahead to life after the pandemic.

Christopher Haiman, ScD

The inequities highlighted in the last ten months have pushed entities to examine their own shortcomings, leading to re-evaluations of risk assessment and care management. For those that are just beginning to study health disparities among their patients, firsthand accounts could prove extremely beneficial.

“If I was just starting from scratch, I would probably want to have an understanding of what these health disparities feel like. That means actually inviting patients and the community to share that,” Medows said.

“We created a webinar series where we invite community patients and some of our own employees to speak about their experiences, and that helps because it makes it real.”

Organizations should also focus on what data they have, Medows added.

“Clinical claims, social factors, community health assessments – even if you don't have a ton of different sources, use what you have to begin building a profile, community by community. If you can at least do that part of the work, as you get more information and more data you can make those communities smaller so that you're starting to focus on families and individuals,” she said.

Data from studies that focus on minority populations can also inform treatment measures and routine clinical care.

“Since there are no ways to prevent prostate cancer, we hope and assume this information will be used for measures of more targeted screening. Maybe men who are at higher genetic risk of developing the disease will be screened, maybe starting at an earlier age and more frequently than men who have an exceedingly low lifetime risk of developing prostate cancer,” Haiman said.

“Of course, then one could think that given the higher risk profile of men of African ancestry, maybe larger proportions of that population will need to be screened earlier. In doing so, we can potentially detect disease at an earlier stage when it's more treatable, and eventually reduce the mortality differences that are observed between populations.”

A lot of health systems will likely take the knowledge and tools they’ve gathered during the pandemic and apply it to situations going forward.

“Because SVI is publicly available to us at the census-tract level, we can use it for other population health questions and programs, like any vaccine rollouts, home-based primary care programs, or transitions of care programs,” Flood said.

“We could potentially use SVI as something to examine and direct additional attention to more vulnerable patients. We’ve learned a lot from this, and we look forward to doing that in the future.”

With all that’s happened in the past year, and with the vaccines on their way, it’s tempting to breathe a sigh of relief and to think that the worst is over. In many ways, however, the work is just beginning.

“We've done a lot, but we still have a long way to go,” Medows concluded.