For Opioids and Substance Abuse, Big Data Analytics Is Just the Beginning

Behavioral health providers are starting to leverage big data analytics to take on the substance abuse ravaging the country, but they need more than health IT to make a difference.

Source: Thinkstock

- Fentanyl, heroin, prescription opioids, and a growing number of synthetic drugs killed more than 50,000 Americans in 2016.

It is a statistic that is hard to compute –numbing in its scope and staggering in the sheer complexity of trying to stem the tide of legal and illegal substances that is drowning a society in crisis.

Breaking down the numbers by state, city, or county doesn’t make it any easier to fathom.

In West Virginia’s McDowell County, 93 out of every 100,000 residents died from a drug overdose in 2016. In Montgomery County in Ohio, overdoses have increased more than six-fold since 2010.

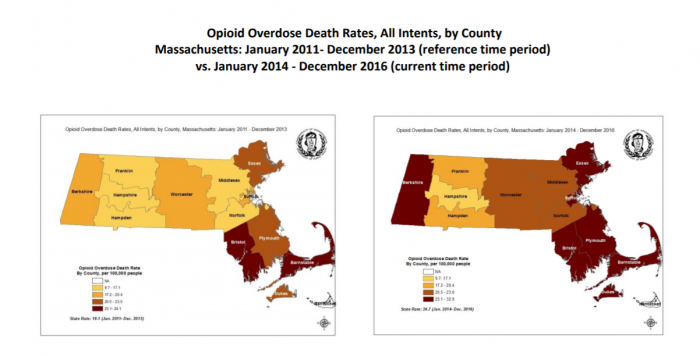

And in Massachusetts, more than 2000 people died from opioid-related causes in 2016.

Between 2013 and 2014, death rates rose by 40 percent – officials are relieved to report that rate has only increased another 17 percent between 2015 and 2016, rising to about 30 fatalities per annum for each 100,000 residents.

Unlike so much other population health data that can lag by months or years, opioid deaths in Massachusetts are hawkishly tracked on a quarterly basis, immediately released to the public in a vain effort to stay one step ahead of the curve.

The dramatic rise in overdose deaths is clear from the maps that get progressively darker as hundreds and then thousands of new fatalities are reported, from the rural Berkshires and elderly industrial towns of Essex County to well-heeled Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard.

Source: Mass.gov

Many of these deaths are attributed to the powerful synthetic fentanyl, which can be up to 100 times more potent than morphine.

The deaths come even after the use of Naloxone, a rescue drug that can reverse the effects of an accidental overdose in minutes.

In the second quarter of 2016 alone, EMS teams in the Bay State were called to 5100 incidents where opioids were suspected or confirmed, representing about 3 percent of all emergency service responses.

More than 4200 of the individuals involved received at least one dose of Naloxone from first responders – over 500 of those cases requires multiple administrations.

For Colin Beatty, CEO of Boston-based Column Health, the charts and graphs represent much more than a grim, abstract recounting of what is happening to other people.

Losing a family member to addiction and mental health issues five years ago has made his mission a personal one.

“We did what most families do: we tried to find adequate treatment for them; we gave no limit to the support that we offered; we threw money at the problem,” he said. “We sent them to the best rehabs available at the time in the world, yet nothing addressed the chronic, recurring nature of the disease.”

Beatty is a button-down-shirt-and-baseball-cap CEO, whose casual demeanor overlays a keen passion and intense focus on his chosen line of work.

“After that family member passed, we were left with the same crushing, nagging questions that about ten families a day start asking themselves,” he said. “Why? Why was the care system failing so miserably? Why were there such glaring gaps in the continuum of care, and why wasn’t technology helping to fix them?”

Source: Mass.gov

At a time when the EHR Incentive Programs was bringing a flood of health IT investment to much of the clinical care continuum, behavioral healthcare providers were being left in the dust.

Largely ineligible for the financial aid available to physicians and hospitals, behavioral healthcare providers have been unable to catch up with their peers in terms of data collection, exchange, and analytics.

“This vertical isn’t what I would call technology enabled,” Beatty observed. “More than half of clinics in the space have absolutely no technology whatsoever – they’re purely paper-based and cash-based. As a result, there’s very little data out there for payers and other stakeholders to use.”

In 2014, just 11 percent of behavioral health providers could exchange any data at all with affiliated or external partners, the ONC says. During that same year, 37 percent of ambulatory providers and 27 percent of hospitals were sharing digital information.

“Every other type of treatment – orthopedics, OBGYN, cardiology, oncology – was benefitting from new systems and new tools to improve quality and outcomes, but substance abuse and behavioral healthcare were being left behind,” Beatty said, his frustration evident.

“We know that it costs the average patient $150,000 a year to get treatment for a substance abuse disorder, but unless we have patient-level encounter data, we don’t know how that money is being spent. We don’t know what’s working and what isn’t.”

The absence of even the most basic patient data isn’t because behavioral health providers and public health officials are taking a lackadaisical approach to the mounting crisis. It’s quite the opposite.

Colin Beatty, CEO of Column Health

Source: Xtelligent MediaColumn Health is adding to its four Boston-area clinic sites as quickly as it can, with plans to open one clinic a month in 2018 across several states in the New England region. The organization serves patients struggling with a variety of substance abuse disorders, from opioids to alcohol.

Its colleagues across the sector are more than eager to use all the analytics and health information exchange tools at their disposal to provide care and recovery services to the thousands of individuals in need.

“There is a desperate desire to share data that is being captured already, and there’s an equally desperate desire to capture more, better, and broader data than we have access to right now,” Beatty stressed.

“There is no shortage of desire among community organizations – public health, first responders, hospitals – there’s no shortage of willingness to commit to this. But we need to take incremental steps, because even though we want to fix everything all at once, this problem is far, far too big for a single massive moonshot.”

Addressing Opioid Abuse with Analytics, Population Health Strategies

Developing Community Partners for Population Health Management

The social and clinical complexity of the substance abuse patient

Primary care and acute care providers are just starting to unpack the idea that the socioeconomic determinants of health play an important role in overall outcomes, but behavioral healthcare providers have been mired in the complexity of this problem since the beginning.

Substance abuse is often just a symptom of very deeply rooted mental health and societal problems that are incredibly difficult to address with traditional rehabilitation techniques.

“A patient can go sit by a pool in Malibu for 28 days, and chances are they’re not going to use substances while they’re in that environment,” Beatty said.

“But on day 29, when they discharge back to their abusive husband, or their apartment with no heat, or that environment where there is easy access to the substances they struggle with…it becomes very difficult to stay in a positive place if they can’t get the treatment they need in their community.”

“Our clinics are built on the idea that people rise to the level of their environment. Meeting people where they are is a key component of treatment,” he said.

Becoming a trusted member of the community can be somewhat difficult for substance abuse clinics. Initial resistance from prospective patients is almost a given, and represents one of the biggest mental barriers to full engagement in therapy.

Substance abuse patients require tailored interventions that take into account the fundamental disinclination of individuals to recognize and address deep-seated behavioral problems.

“A lot of the work we do absolutely has to be done face-to-face,” said Amanda McCarthy, Manager of Community Outreach at Column Health.

“It has to be personal. If we’re not immersed in the community in a way that builds trust and makes people confident that we’re here to help, we’re not going to get our job done.”

Building rapport with individuals one-on-one is essential for convincing skeptics that treatment can really work, she added.

Amanda McCarthy, Manager of Community Outreach

Source: Xtelligent Media“If we don’t create that trust, we won’t be able to convince them that this model works and that we’re not going to judge them or yell at them or look down on them because they’re struggling with a disease.”

“That’s why we invite people into our space, and why we try to make our clinics a really warm and positive environment so we can build that comfort and that trust that helps individuals open up and receive the care and changes they need to get better.”

At Column Health’s Davis Square location in Somerville, a storefront window opens on to a miniature gallery space. The walls are covered with artwork depicting vintage sports teams.

Individual treatment rooms line a hallway leading to an open-plan kitchenette and a community room that hosts yoga classes, family support groups, and other events.

Everyone is offered a bottle of water upon arrival, wrapped in a Column Health label. The act of handing over even such a small token is a way to make a connection between one person and another, Beatty says, to show concern and care.

Patients who commit to treatment spend a lot of time in that space with their clinicians, especially at the beginning of the high-touch recovery process, which makes it important to provide an environment that encourages patients to feel comfortable and secure.

“The first phase of treatment starts with a higher-frequency schedule at the beginning for the first eight weeks, because that’s when a patient is at the greatest risk of a relapse,” Beatty explained.

“And then if the clinician and patient decide that they’re ready to step down to phase two, they might come in for four or five visits spread over two weeks as they get more stable. Then we can move to the third phase, which could be once a month. We aim to maintain stability for our patients throughout that process, and we track their progress to see what strategies and modalities are most effective.”

Source: Column Health

The location is also equipped with the ability to collect blood samples from patients, which helps Column Health identify and address health issues that may be related to substance abuse but aren’t directly behavioral in nature, such as diseases commonly acquired from shared needles.

“We do Hepatitis C and HIV screenings on intake for every patient,” said Beatty. “We’ve found around 20 patients so far that were not previously diagnosed with Hepatitis C. That means we can get them on a cycle of pharmacotherapy and save their liver.”

“That’s pretty darn good for the patient – and it’s also very attractive to their payer, who doesn’t have to pay a million dollars for a liver transplant somewhere down the line.”

“Our clinics are built on the idea that people rise to the level of their environment. Meeting people where they are is a key component of treatment.”

Column Health may be physically immersed in the community, but creating a collaborative big data environment in conjunction with public health agencies, complementary providers, and health insurance payers is another critical challenge.

“We’re going through an interesting struggle – and it’s certainly indicative of the broader market – about how to marry the brick-and-mortar presence of a substance abuse clinic with the data we need to support the best possible care we can give,” Beatty said.

Despite the state’s effort to push out as much information as possible to stakeholders, the overall scarcity of data collection and sharing infrastructure is hampering efforts to get a handle on the true magnitude of the opioid crisis in the Boston area and beyond.

“Public health and community entities like police departments are still in the beginning stages of collecting data,” explained McCarthy. “They collect it department by department and town by town, but it isn’t centralized yet. We’re trying to create a broader database where we can all see each other’s data and use our tools to connect with the community in a stronger way on a day-to-day basis.”

Beatty believes the responsibility for leading that process falls on the shoulders of providers and their health IT partners, not necessarily the public health agencies themselves.

“We find that we can’t expect a lot of entities in this space to do the data collection piece of the puzzle,” he said. “That’s not their core competency, and it’s not what they have the staff to do. I hope that police departments never focus on informatics as their core competency. It’s not their job.”

“It’s our job to go into those environments and collaborate with those entities so that we can all do what we’re best at to get where we need to be. Our goal is to get every patient into the right level of treatment, and we need all of our partners to focus on helping each other do that.”

Maintaining the division of labor required to complete the complex process of guiding a patient through their optimal treatment program helps prevent any one member of the team from feeling overwhelmed by the sheer enormity of the work required to make a dent in the substance abuse epidemic.

“We don’t want to be so completely consumed with the urgency of day-to-day operations that we lose sight of how to move forward long-term,” Beatty said.

“We can start with the little things that are possible in today’s world: setting up a 24-hour help line for individuals or exchanging the handful of basic datasets we can share easily without business associate agreements between all the players. Those are things we can do that address the urgent without losing sight of the important.”

Using Risk Scores, Stratification for Population Health Management

Mental Health Patients Receive Half of All Opioid Prescriptions

Using the cloud to create an umbrella of data availability

Individuals struggling with substance abuse commonly lead lives filled with uncertainty: fluctuating job schedules, housing instability, or family care needs that make it difficult to maintain a regular treatment schedule at a single location.

Loss-to-treatment, due to transience and other obstacles, is a significant concern for behavioral health providers, who use their rate of attrition as a primary quality measure.

“Loss-to-treatment is one of the most critical variables in this space,” Beatty stressed. “You can’t get a patient well if they’re not coming in to treatment. Often times, these patients simply disappear. It could be because they move away, because they pass away, or because they think they’re getting better and don’t need the help anymore.”

“The market average for loss-to-treatment is about 45 percent a month. That’s massive – that’s absolutely catastrophic if you think about it.”

But low-income patients who can’t afford child care or a few hours off of work aren’t the only ones at risk of falling away from their care plans.

“A lack of stability due to socioeconomic hardship is definitely a major concern,” said Beatty. “But at the other end of the spectrum, we have the uber-wealthy who are spending their summers on the Cape or traveling internationally, and those people can also have difficulty maintaining a regimen.”

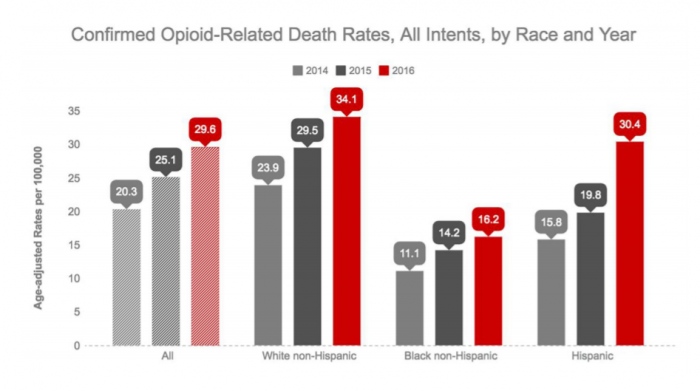

Opioid abuse in particular rarely discriminates between social and economic classes – individuals with higher levels of education, Caucasian heritage, and addresses in higher income areas are actually more likely than other groups to receive opioid prescriptions when presenting in the emergency department, despite similar levels of pain.

“To be able to offer treatment to patients at both of those extremes, you need to be able to coordinate care between different clinic sites and have a contiguous and fluid experience for them even if they seek care in a different town or city.”

Cloud-based health IT tools are essential for enabling that seamless approach to care, says Jim McIntyre, Column Health’s Chief Marketing Officer.

“Pushing data to our clinicians allows us to operate beyond our size and our scale,” he said. “We’re a network of outpatient behavioral health clinics, but we like to see ourselves operating more along the lines of an academic medical center.”

“The data we give our clinicians enables complex case review and grand rounds. It enables care coordination. It lets them work together and operate in a different way than our peers.”

Column Health uses technology from a Massachusetts neighbor, athenahealth, to support its cloud-based approach.

Jim McIntyre, Chief Marketing Officer

Source: Xtelligent Media“In the same way that we can confidently tell our patients that they’re not alone and they can rely on us, we tell our clinicians that we’re here to support them with the data and technology they need to excel at their work,” said McIntyre.

“That approach is why our care model has been so successful, and why we’ve been able to bring better outcomes to our patients while staying very financially secure.”

Clinicians can access an individual’s health record in any of Column’s locations, which makes it much easier for patients to pick up where they left off, no matter where they are when they decide to re-enter their program.

“It would be incredibly labor-intensive to provide that same level of continuity without a cloud-based system,” Beatty notes. “We would be running up against a huge frictional loss of information and granularity and clarity.”

“We know that there will always be a loss of precision and accuracy when data is translated and transcribed and moved back and forth without the right tools, and we really need to avoid that in this line of work.”

“The market average for loss-to-treatment is about 45 percent a month. That’s massive – that’s absolutely catastrophic if you think about it.”

This safety net of patient data, coupled with some basic analytics on risk and behavioral patterns that can help to preempt no-shows, has immediate and impactful results.

Column Health’s loss-to-treatment rate hovers around three percent, dramatically lower than the national average. Its no-show rate is around 17 percent, less than half of what the rest of the market typically experiences.

Forging payer partnerships for value-based behavioral healthcare

Working with a payer who has similar goals and understands the challenges of the behavioral health space has been one of the keys to Column Health’s success.

The organization’s proactive, high-touch, data-driven approach to substance abuse treatment lends itself well to the burgeoning value-based care environment, and encourages financial alignment between payers and providers.

“Payers are starting to realize that being proactive about care reduces the overall cost to cover a life,” Beatty noted.

“If a patient comes to us and does well in treatment and recovery, that means they are more likely to avoid those high-cost clinical event horizons – the overdoses, the liver transplants, the heart valve transplants – that are both catastrophic for the patient and extraordinarily expensive for the healthcare system.”

Column Health works closely with Beacon Health Options, which maintains a sharp focus on the behavioral healthcare space.

Bundled payments are an area of financial opportunity for both sides of the equation, but both entities had to agree upon working definitions of positive outcomes before they could engage in payments for these episodes of care.

“Pushing data to our clinicians allows us to operate beyond our size and our scale."

Quality metrics and performance thresholds are difficult enough to define in the clinical environment, even when objective measurements like lab values or blood pressure readings are available to sort patients into “controlled” and “uncontrolled” buckets.

For the incredibly individualized discipline of behavioral health, the notion of what counts as a “success” is even murkier.

“If you ask ten different people, you’ll get ten definitions for what constitutes a relapse,” Beatty acknowledged. “There are some folks who believe in substance abstinence only. Others believe that it only matters if it’s the particular substance of interest. Still more will say that a relapse is only when a patient requires a change in the level of their care.”

Beacon and Column collaborated to come up with two main categories of what they would consider a relapse. Transient relapses are relatively minor slip-ups that do not result in loss-to-treatment or don’t require major changes to the care plan.

Source: Column Health

“It’s definitely important to note them in the care record and integrate that into the treatment plan, but if a patient can self-identify that they’re slipping or they’re using a different substance, we don’t consider that a major relapse,” Beatty said.

The second category is more serious: a significant relapse would mean that the current level of care is no longer suitable for the individual’s needs. That is an important distinction for a bundled payment program, Beatty says, since it often marks the transition to a more expensive inpatient treatment plan that must involve a separate, specialized provider.

Column’s patient cohort receiving care in conjunction with Beacon has relatively low rates of both types of relapse, he said, and the two partners are looking to expand their capability to engage in value-based payment models.

“We want to progress to include all of the additional components and different modalities as we identify appropriate clinical pathways that have improved outcomes for specific subpopulations of patients,” said Beatty.

Moving to the next level of value-based reimbursements will require an even greater investment in leveraging Column’s existing data assets as well as cultivating new approaches to predictive analytics and quality reporting.

Relapse prediction would be the Holy Grail for behavioral health providers, Beatty says, as well as the payers who are looking to trim costs from across their coverage areas.

“Data is very valuable to identify what modifications we need to make to existing best practices so we can get more tailored, more granular care that not only suits patients better, but allows us to move further into risk sharing with our payers,” said Beatty.

“If we could start to do predictive analytics reliably and accurately by taking a page from retail and start to understand the behavior patterns that might indicate a person is at high risk of addiction or that they are about to relapse, that would be the most fantastic thing.”

Key Strategies for Succeeding with Healthcare Bundled Payments

Good Data, Better Value-Based Care Can Boost Population Health

Architecting a new future for substance abuse treatment

Attaining that vision seems much more likely now than it may have a few years ago, before machine learning and other advanced big data analytics techniques started in earnest along the road to maturity.

Like many other provider organizations, Column Health is starting to investigate how the nascent machine learning segment could support its efforts to target individuals further upstream, lowering long-term costs and improving the quality of life for patients.

“We’re working with a couple of our partners to drive some simple machine learning and predictive analytics into our combined data sets,” said Beatty. “That data can be used to predict the risk of relapse at the point of service.”

“That becomes a profound disruption in this vertical and a major opportunity to change people’s lives. If we can start to predict and prevent instead of chase and treat, then we start drastically accelerating the impact we can make on entire communities.”

Ideally, Beatty would like to see better big data analytics render his expanding network of clinics obsolete.

“No matter how robust, ethical, and mission-driven our current models of care are, nothing would make me happier than if we could stop using them and transition instead into forestalling those spirals of addiction and focus on keeping patients healthy instead of reacting to when they enter a crisis,” he said.

“The real trick is to identify the things we don’t know yet about substance abuse, but that are there in the data for us to discover. That’s where it becomes exciting, and that’s where even very simple natural language processing and machine learning can help us out.”

"If we can start to predict and prevent instead of chase and treat, then we start drastically accelerating the impact we can make on entire communities.”

The current lack of data analytics and health information exchange infrastructure may be a blessing in disguise: unlike the clinical care continuum, which has painted itself into a corner during its long, staggered, and haphazard effort to upgrade its technology piece by piece, the behavioral health space as an opportunity to start from scratch.

Hospitals and physician providers certainly haven’t worked out all the kinks in their electronic health record and analytics systems, but they have identified many best practices that they wish they had known earlier.

Behavioral healthcare providers can take advantage of these lessons learned to start developing a data-driven system that brings value to patients, providers, and payers equally.

“If we’re not trying to move into predictive analytics, then we’re missing a good opportunity to put all this data we’ve been collecting to its best possible use,” Beatty said. “Getting there is going to mean collaboration. It’s going to mean transparency, and it’s going to require us to learn from each other and borrow the best of what we’re doing from each other.”

Behavioral healthcare has another unique advantage, he added, even if it is a lamentable one.

“There is basically no competition in the substance abuse environment,” he said. “We can’t open enough clinics. We can’t do it fast enough. I could open a clinic on every block in Boston without putting a dent in the demand we have. Every place we go, the epidemic has already reached plague proportions. That’s a sad reality, but it’s where we are as a nation. “

“Because we don’t have to worry about being jealous about our market share like other healthcare verticals, we have a lot of opportunities that aren’t there in primary care or acute care,” he continued. “And because there is such urgency in this area, we have to be willing to work together to get those best practices out there.”

“We can’t open enough clinics. We can’t do it fast enough. Every place we go, the epidemic has already reached plague proportions."

Beatty is incredibly eager to continue forging those partnerships, both locally and across the country.

Experts often say they’re willing to share their strategies and lessons learned with their peers, but Beatty is unreservedly, infectiously enthusiastic about doing whatever he can to help other organizations start getting to grips with the rising toll of opioids and other substances on their communities.

“Call me. Talk to me,” he urged. “I mean it. I will share every aspect of what we’re doing – and most of it isn’t unique or especially complicated – so that other people can make the changes they need without reinventing the wheel. We’ve got a wheel for you.”

“We love helping other organizations move down that pathway, even if we're not in their back yard. And if they are in our back yard, all the better, right? We need to start to coordinate care – and we can actually start to move the needle on this massive problem that everyone, everywhere is affected by in some way if we implement the right programs with strong partners and good data to support them.”